Barbara Collins was waiting in the kitchen when her husband of 50 years walked out into the backyard and shot himself.

Barbara Collins was waiting in the kitchen when her husband of 50 years walked out into the backyard and shot himself.

He had woken her that morning, a mild summer day at their home in Raymond Island in the Gippsland Lakes. They had sat together in the living room and said their final goodbyes.

When it was time, he hobbled outside on his crutches and collected his gun, locked away in the safe stored in the garden shed.

Robin Collins’ body would lie on a patch of grass, near the Hills Hoist, for about 30 minutes before the police arrived.

Later, forensic cleaners would do their best to wash away all evidence of the shooting. But there was a piece of grass where his blood and other body matter remained, so they cut it away. For months, Barbara had to water the newly sown piece of lawn.

That final morning, Barbara had stayed inside the house, as Robin had requested. However, when she called triple zero, they asked her if she could look into the backyard to see if her husband was moving.

The sight of him lying in the grass continues to play over her mind, but as she said last week: “When the police arrived, sirens blazing, all I could think was: ‘He’s not suffering anymore’.”

There’s a palpable anguish that comes with knowing someone you love has lost their will to live; that the fear of dying a painful death riddled with disease has overtaken their desire to keep going.

As a father, husband, and engineer, Robin had always been stoic and determined. Other men might be handy with their tools, he forged his own out of iron. He built boats, and was a champion sailor. He built a plane, and he and Barbara flew around Australia.

He was also not one to talk about pain. So when he got sick with myelofibrosis, a form of blood cancer, his family could only helplessly observe his decline. His daughter Amanda Collins knew that her father was likely to shoot himself. She just didn’t know when.

“My dad was always a law abiding man. He owned guns and taught us to use and to store them responsibly,” Amanda said.

“He refused to implicate any of us in his death, especially my mum. But he knew that he couldn’t tolerate any more days of utter misery.

“So my darling dad was alone at the most terrifying moment of his life. To this day I don’t know how he had the courage to do it.”

Robin Collins’ story is emblematic of an unavoidable reality: that many terminally ill Victorians are choosing to end their lives, rather than endure the intolerable suffering they expect to face in its final stages.

Sometimes that death is aided and assisted: the growing number of people who have sought advice on how to illegally obtain barbiturates over the internet; the doctors who covertly adhere to their patients’ request for terminal sedation or a lethal dose of drugs to hasten their death.

And in recent years, there’s been an emerging trend of people inhaling a certain chemical that has traditionally been used for home brewing, but is now marketed as a deadly gas by a company affiliated with pro-euthanasia group Exit International.

But far too often, that death is solitary and violent. Figures from the Victorian Coroners Court suggest that 240 people who experienced “irreversible decline” in their physical health took their own life between 2009 and 2013.

There was the 90-year-old man who had lived his life as though it was a gift, but killed himself with a household tool after the melanoma spread to his brain.

There was the 59-year-old cancer patient who underwent 22 cycles of treatment, but was later found by a motorist under a bridge on a major Victorian freeway.

And there was the 82-year-old woman with a long medical history of hypertension, insomnia, arthritis, and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, who bled to death. She had lost her eyesight – and with it, her ability to read books, which had always been her joy.

Fairfax Media has chosen not to include some of the raw details of the Coroner’s evidence, much of which was so shocking it profoundly shaped the parliamentary inquiry that would ultimately form the basis of Victoria’s euthanasia reforms.

Coroner Caitlin English told the inquiry at the time: “These are people who are suffering from irreversible physical terminal decline or disease, and they are taking their lives in desperate, determined and violent ways.”

With Parliament on the cusp of debating the country’s first state government-sponsored assisted dying bill, advocates for reform hope the laws will result in fewer people choosing to die in such harrowing circumstances.

Instead of turning to “backyard euthanasia”, terminally ill Victorians will have access to physician-assisted death in strictly defined circumstances, giving them the chance to die in peace, at a time of their choosing, in the company of their loved ones.

Some might not go through with it in the end: since the Dying With Dignity Act was passed in Oregon 20 years ago, 1749 people have had prescriptions written under the law, but only 1127 patients had died from taking the medication. Proponents believe that simply having the choice will make all the difference.

“The evidence overseas is that many people that apply may not end up using the assisted dying to end their life, but it is the assurance that it brings them – with how to get through today, and how to get through tomorrow and how on earth to get through the day thereafter,” said Health Minister Jill Hennessy.

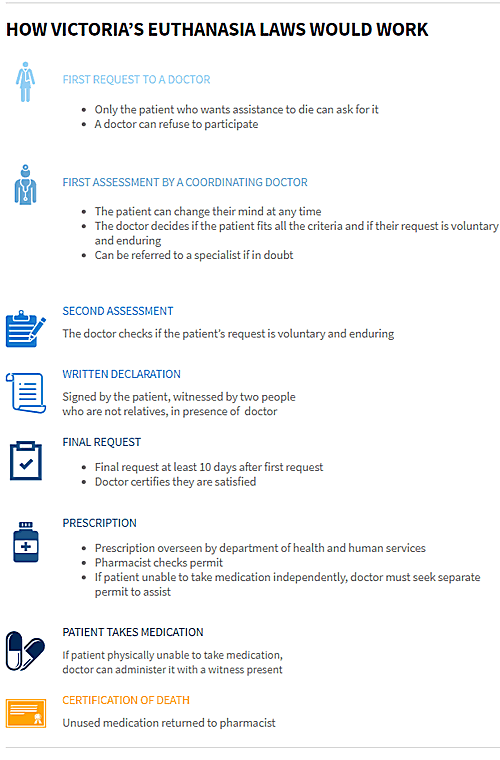

Under legislation to be debated this month, adults who are terminally ill, have no more than 12 months to live, and still have decision-making capacity will be eligible for a lethal pill – most likely to be a newly created concoction of drugs already approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration.

In order to qualify, a patient must be a permanent resident of Victoria, must make three requests (two verbal, one written) and must obtain approval by two doctors, including one who specialises in their illness.

With 68 safeguards enshrined in the bill, Premier Daniel Andrews insists the reforms would be the “most conservative” in the world. But not everyone is convinced.

Some do not wish to see assisted dying legalised at all. Others who support it warn against creating a new pill through a “cocktail” of TGA-approved drugs, and have instead urged the government to use Nembutal, a fast-acting barbiturate that has been used in other countries for years. And some say the legislation is so heavily safeguarded that few people will qualify, forcing them to find other options.

Take the Coroner’s findings as a case in point. Of the recorded suicides involving people in “irreversible decline” due to disease, about half were diagnosed with cancer. Depending on how long they had to live, many of those people could have been eligible for an assisted death under the proposed Victorian regime.

But the other half ranged from patients with multiple sclerosis, prostate issues, lumbar spinal osteoarthritis and so on – conditions that can diminish one’s quality of life, but would not necessarily meet the criteria for assisted dying under the government’s model.

Controversial euthanasia advocate Dr Philip Nitschke argues the reforms are so onerous that he expects there will still be a “strong and growing demand” to illegally access euthanasia drugs over the internet, where 25 grams of Nembutal can be sourced for about $700 from places such as China or South America.

In a sign of that demand, Australian Federal Police data reveals approximately 10.4 kilograms of Nembutal has been seized by authorities since 2013. But as Nitschke knows only too well, plenty more slips through the cracks.

For years, Nitschke’s group Exit International has been holding workshops advising mostly elderly people about end-of-life matters: from how to buy the drugs online using bitcoins and encrypted emails, to the prevalence of certain deadly gases. The last 10 workshops held across Australia between August and September attracted about 1500 people, he says, “and many of them already had their drugs”.

“The average age [of participants] was about 75 years old – they’re basically people who want to know what their choices are, and more particularly how they can hold of all the best drugs,” Nitschke told Fairfax Media from Amsterdam this week. “That’s a common question: how do I obtain these drugs and keep them just in case? They want to know they’ve got the safety net in place.”

Melbourne urologist Rodney Syme, who has been advocating for assisted dying for decades, takes a somewhat different approach. Syme estimates he’s counselled about 1800 people about end-of-life matters, and now receives “about three to four approaches a week” for advice.

Like Nitschke, he is concerned that many people won’t qualify for an assisted death under the Victorian model, but adds: “You have to start somewhere.”

What’s more, he argues, passing the bill will lead to much broader discussions between doctors and patients about the end of life – the kind of conversations that are currently limited because of uncertainty in the law.

While the Crimes Act stipulates that suicide is not a crime, doctors or family members involved in killing or helping to kill someone with a terminal illness are at risk of being charged with murder (maximum penalty life imprisonment) or aiding and abetting someone to suicide (maximum penalty five years’ imprisonment).

However, prosecutions are rare: between 1992 and 2013, 10 people were charged with offences related to assisted dying, including five cases of attempted murder, but none received jail terms.

Victorian cases relating to assisted dying

For example, in 2013, Heinz Karl Klinkermann was convicted of the attempted murder of his then 84-year-old wife, Beryl, who was suffering advanced Parkinson’s disease and dementia, and could no longer communicate.

After researching suicide on the internet, he gave her a sleeping pill and took several himself before he laid down holding her hand and they were poisoned with carbon monoxide. They were later discovered by a district nurse.

An intervention order was later taken out preventing Klinkermann seeing his wife in palliative care. In sentencing him, Supreme Court Justice Betty King said it was clear he adored his wife, and this restriction was “in some ways the worst punishment that could be made”.

The legal uncertainty is also problematic for the medical profession, where voluntary euthanasia sometimes takes place, albeit covertly.

Long-term palliative care nurse Lynette Dickens – who is opposed to assisted dying – said she often hastened people’s deaths, in the process of giving them drugs to relieve their pain.

“I can honestly say I have never intentionally murdered anybody, but I have certainly made a lot of people comfortable so they die peacefully,” she said. “It’s a bit of a joke really. We all know that it goes on, but no one admits to it.”

But while doctors can invoke the “doctrine of double effect” as a defence – which generally accepts that whatever treatment is needed to alleviate suffering is permissible, even if the outcome happens to be death – concerns remain.

Syme says the government’s bill will lead to much greater clarity in the law – and much-needed choice for patients.

“Most doctors run a mile before they engage in an honest, open discussion with all the cards on the table – because if you don’t have the opportunity to provide assisted dying, all the cards aren’t on the table,” he said.

“The great thing this legislation will do is open the gates to broad discussion between doctors and patients about the end of life, and as a result, many of those people who might otherwise end their lives as the Coroner has described will not do so.”

Rob also wonders what might have been had assisted dying been legal on February 27, 2014, when her father Robin, 73, took his life.

On the death certificate issued after her father’s death, it says Robin died of a gunshot wound. In reality, he was also “several excruciating weeks” away from dying, Amanda said.

His spleen had gotten so big he couldn’t breathe, sit or lie comfortably and his stomach was also compressed, which meant he could not take in much food.

“So he was basically going to just starve,” Amanda said. “The only thing he would say was ‘If I was a dog, you wouldn’t let me suffer like this’.”

Amanda believes her father would have sought and been granted access to euthanasia drugs if they were legal at the time of his death.

Significantly, she also feels that had her father had access to lethal medication, he might have never killed himself, but died in a hospice surrounded by his loved ones, knowing he could say goodbye at a time of his choosing.

“He would have been grateful for the gift of a dignified end, rather for the nightmare he left for my family.”

Victorian cases relating to assisted dying

R v Hollinrake, 1992

Charge Attempted murder

Maximum penalty 25 years’ jail

Actual penalty 3-year good behaviour bond. Jean Hollinrake had long expressed horror at the thought of becoming impaired and losing control of her senses. When she suffered a debilitating stroke, her husband of 51 years, who had suffered health issues himself in the preceding decade, set about honouring a pledge to her and unsuccessfully tried to end both their lives. Justice Coldrey said that, in such “truly tragic” circumstances, justice may be “tempered with mercy”. “I cannot accept that the community would want a sentence involving retribution in the circumstances of this case.””DPP v Riordan, 1998

Charge Attempted murder

Maximum penalty 25 years’ jail

Actual penalty 3-year good behaviour bond. Riordan tried to kill himself and his wife, who was suffering from advanced Alzheimer’s. Justice Cummins stated: “Mr Riordan is a decent, compassionate and selfless man who was totally devoted to his wife. He spent his life working hard and caring for his family … Ultimately … he sought to take his wife’s life to relieve her of the terrible suffering and indignity she had been undergoing for years and which he daily saw.”

R v Marden, 2000

Charge Manslaughter by suicide pact

Maximum penalty 10 years’ jail

Actual penalty 2-year suspended sentence. Robert Marden tried to kill himself and his wife of 48 years, Joan, who was suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, was unable to dress herself and was in constant pain despite medication. Several times she had expressed a wish to die. Mr Marden had undergone surgery to have a pacemaker implanted but was later diagnosed with lung cancer and depression. The couple decided to die together. Joan died but Robert’s pacemaker kept him alive. The judge accepted a statement from their son that “he did what he did to my mother out of the uncompromising love and devotion he had for her”.

R v Hood, 2002

Charge Aiding and abetting suicide

Maximum penalty 5 years’ jail

Actual penalty 18-month suspended sentence. Daryl Colley believed that he had a terminal illness and wanted to take his own life. A friend who had tried to talk him out of it eventually agreed to be present as he consumed drugs and alcohol. Justice Coldrey said, “The degree of moral blame attributable to a person who assists or encourages an act of suicide may vary greatly from case to case. At one end of the spectrum may be placed a person who assists or encourages a person to commit suicide in order to inherit property or for some other ulterior motive; at the other end there is the individual who supplies potentially lethal medication to a terminally ill person, perhaps a loved one who is in extreme pain and who wishes to end that suffering at the earliest possible opportunity. I regard your case as being some way towards the latter end of this spectrum.”

R v Maxwell, 2003

Charge Aiding and abetting suicide

Maximum penalty 5 years’ jail

Actual penalty 18-month suspended sentence. Mrs Maxwell had terminal cancer. Her husband had tried to dissuade her from taking her own life several times and had looked for herbal remedies for her without success. She decided that she wanted to die using a method she read about but she needed her husband’s help to carry out the method. In sentencing Maxwell, Justice Coldrey said: “I do not believe that thoughtful members of the community, knowing all the facts relating to you personally and the unique circumstances of this tragic case, would regard your immediate imprisonment as necessary. In my view, this is a case where justice may be tempered with mercy.””

DPP v Karaca, 2007

Charge Attempted murder

Maximum penalty 25 years’ jail

Actual penalty 3-year suspended sentence. A man suffering repeated bouts of depression convinced his two housemates to accompany him when he set about ending his life. He had requested that, if he was unsuccessful, his friends should hit him to kill him. One of the men struck him twice. The judge took into account multiple mitigating factors and said the housemates had been manipulated to assist the man in his plans for suicide.

DPP v Rolfe, 2008

Charge Manslaughter by suicide pact

Maximum penalty 10 years’ jail

Actual penalty 2-year suspended sentence. Janetta Rolfe had vascular dementia, needed help to walk and could no longer communicate. Her husband of 55 years, Bernard, worried that she would go into respite care and that they would be separated. He suffered extreme anxiety and depression. He promised her that she would not end up in a home. When police found the couple at home, Janetta had died but paramedics resuscitated Bernard. In sentencing him, the judge said, “Your actions do not warrant denunciation; you should not be punished; there is no need to deter you from future offences; and you do not require reformation.”

DPP v Nestorowycz, 2008

Charge Attempted murder

Maximum penalty 25 years’ jail

Actual penalty 2 years and 9 months suspended sentence. Mrs Nestorowycz tried to kill herself and her husband who was suffering from dementia and diabetes and living in a nursing home. She was found to have been suffering from a major depressive disorder at the time and said to have had reduced capacity to make appropriate decisions.

Victor Rijn, 2011

Charge Inciting suicide

Maximum penalty 5 years’ jail

Actual penalty 3-year good behaviour bond. Inger Rijn developed chronic pain from a tendon tear in her hip that resisted medication and other alternative therapies. She died alone at home using aids that her husband, Victor, had bought online from a voluntary euthanasia group. He had told his defence barrister, “You come to a point where you don’t want to lose your wife who you love but you also don’t want to see her suffer as much as she was.” A magistrate said there was little doubt Inger Rijn’s decision to end her life was her own, made with a sound mind. He said Victor Rijn was a decent man whose moral culpability was at the lower end.

R v Klinkerman, 2013

Charge Attempted murder

Maximum penalty 25 years’ jail

Actual penalty 18-month community corrections order (was also prevented from seeing his wife). After researching suicide on the internet, Heinz Karl Klinkermann attempted to kill himself and his wife, Beryl, who had advanced Parkinson’s disease and dementia. Klinkermann gave his wife a sleeping pill and took several himself before they laid down together holding hands and were poisoned with carbon monoxide. They were later discovered by a visiting nurse.

Stay Informed. It’s simple, free & convenient!