Dinesh Munasinha

Latest posts by Dinesh Munasinha (see all)

- Divorce and Property Dispute: Preparing for Litigation - July 30, 2015

- Everything you need to know about Family Trusts: Part 2 – Avoiding Pitfalls - November 8, 2014

- Everything you need to know about Family Trusts: Part 1 - August 21, 2014

The notion of having a Family Trust is viewed by many as too complicated, prone to high risk, a facilitator of family disputes and with little to ultimately gain in financial terms.

The notion of having a Family Trust is viewed by many as too complicated, prone to high risk, a facilitator of family disputes and with little to ultimately gain in financial terms.

There have also been a number of high profile cases in the public domain of Family Trusts that have not been set up or managed properly, at times leading to significant tax penalties and family disputes for those involved.

However, it need not be that way.

For those who set a Family Trust properly , it is considered one of the best legal tools to help better distribute the wealth of the family and make substantial tax savings at the same time.

And in times of separation, family disunity or conflicts, a Family Trust can also play a vital role in the protection of assets.

In Part 1 of this Article we will try to understand what a family trust is and its advantages.

In Part 2 we will look at the tool box required to set up a family trust and the possible pitfalls to avoid.

PART 1

What is a Family Trust?

A family trust could be loosely understood as a mechanism used to collect money and assets for the benefit of the family members. Hence, the assets in the family trust may it be cash or property, is not held in any individual names of family members but are held in the trust.

A Family Trust is also a variant of a “discretionary trust”, which means the trustees have the right to distribute the trust property in a manner they deem fit.1

There is some terminology jargon used in the law of trusts which is worth understanding at the outset;

TRUST DEED: A trust is created by drawing a “Trust Deed”. The Trust deed states the terms and conditions under which a family trust is established and maintained.

Importantly this deed sets out the powers of the Trutees as well. This is usually drafted by a lawyer after discussing the purpose of the trust with their clients.

The trust is established by the trust’s “Settlor” and “Trustee” (or trustees) signing the trust deed, and the settlor giving the trust property (the “settled sum”) to the trustee.

SETTLOR: The “Settlor’s” function is to give the assets to the trustee to hold for the benefit of the trust’s beneficiaries on the terms and conditions set out in the trust deed. The settlor executes the trust deed and then, generally, has no further involvement in the trust.

TRUSTEE: The “Trustee” is responsible for the trust and its assets. The trustee has broad powers to conduct the trust, and manage its assets but limited to the terms and conditions stipulated in the trust deed.

In a family trust, the trustees are usually the parents (or a company of which either both or one of the parents is a major shareholders and/or director). Their children and any other dependants are usually listed as beneficiaries.

How Does a Trust Become Recognised as a Family Trust for the Purpose of Tax Law?

To be treated as a family trust for tax purposes, the trustees have to complete a ‘Family Trust Election’ (FTE) and limit the beneficiaries to eligible family members. The FTE must nominate a ‘test individual’ who is to benefit from the trust and specify an income year in which the trust is to start.

The test individual will usually Settlor and the family group can include:

i. Any parent, grandparent, brother, sister, nephew, niece or child of the test individual or the test individual’s spouse; and

ii. A range of other family members, as defined in section 272-95 of Schedule 2 F of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936. 2

In addition to making an FTE, specific provisions need to be included in the trust deed that provides the trustees with their discretionary powers and ensure the beneficiaries do not have a fixed entitlement to income and capital from the trust.

What are the Advantages of a Family Trust?

The more obvious advantage accountants and financial advisers emphasise are its tax advantages. Whilst this is very important, one should not lose sight of the other advantages of easier distribution of wealth. In this section I will discuss both these aspects.

- A family trust could help the family to distribute their income in a manner which ensures that the tax liability of the family as a whole are reduced.

- It could act as a device to plan the distribution of the estate at death.

- It can also assist in protecting the family group’s assets from the liabilities of one or more of the family members (for instance, in the event of a family member’s bankruptcy or insolvency).

- A method of assisting family members with lesser assets as retirement plan.

Let’s discuss some of these in greater detail.

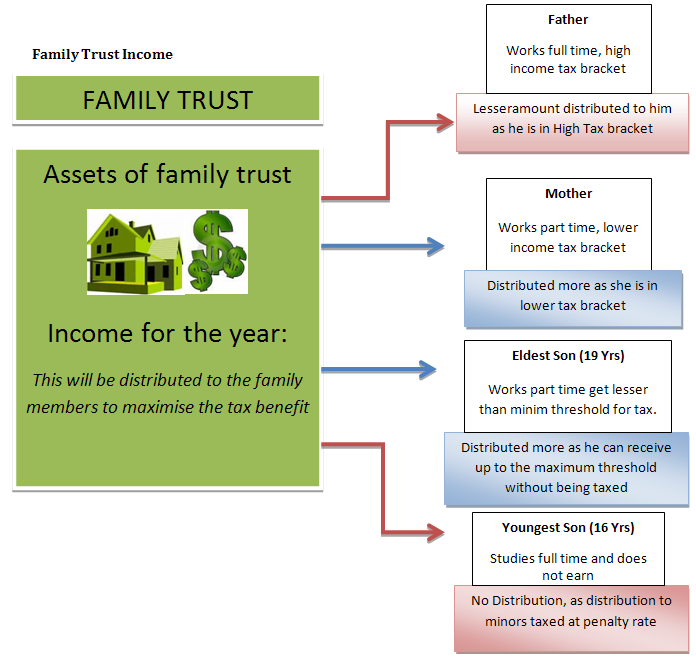

The above diagram depicts the way in which the income and the tax structure works in a Family Trust.

The Trust could be used to own assets like the house or shares etc. The income the trust receives should be distributed to family members in the proportion the trustees may decide.

However, it must be stated at the outset, the Trustees need to bear in mind that the key objective of the family trust should not be simply to avoid taxes, otherwise, it would violate the anti-avoidance provisions in Part IVA of ITAA 1936 3

Deciding how to distribute Family Trust Property

In deciding how to distribute the property three key aspects must be considered;

a) Make sure that all income is distributed: A trust itself does not have to pay income tax on income that is distributed to the beneficiaries, but does have to pay tax on undistributed income. Undistributed income is taxed in the hands of the trustee at the top marginal tax rate plus medicare levy which is 46.5% in the current financial year.

A trust itself does not have to pay income tax on income that is distributed to the beneficiaries, but does have to pay tax on undistributed income.

b) The proportion of distribution should best be considered in line with the receiver’s marginal tax rate – in the previous example the father is the high income earner. Hence, its best to distribute more to the wife who is only working part-time.

c) Do not make distributions to non-family members and try to avoid minors – It goes without saying a family trust needs to ensure that they satisfy the family trust election (FTE).

Therefore, it can only be distributed to the family members. However, if the family member is a minor, any distributions made to the minor will also be taxed at penalty tax rates and should be avoided.

Distributions received from a trust are not a special form of income, but instead forms part of a beneficiary’s assessable income. If the beneficiary receives income from other sources in addition to distributions from the trust, all of the income will be taxed together.

On a separate note, one must bear in mind that there is capital gains tax on sale of assets by the Trust. However, there is a 50 per cent discount on realised capital gains where trust assets have been held for more than 12 months.

Trust beneficiaries are generally required to submit a tax return, unless they are eligible for an exemption, and the trustees should provide details of the income distributions to beneficiaries to assist with their tax affairs.

Estate Planning Tool

Some wealthy parents who have children who are viewed as spendthrifts or prodigals prefer to leave their assets in family trust rather than bequeathing them by will. They usually prefer to establish a trust upon their death naming a matured friend or relative as the trustee so that they can devise the money to their children based on their needs, rather than allowing the children to reach it as a lump sum.

In the event there is already a family trust in place, the beneficiary must remember that he or she cannot bequeath trust property by his/ her last will. The trust property as we have discussed earlier is not actually of the beneficiary but only of the trustee. What happens to the trust property or the portion of income to the beneficiary upon the death of the beneficiary will only be decided by the Trust Deed for the Family Trust and not the last will of the beneficiary.

Asset Protection

Asset protection becomes distinctly important in two instances i.e bankruptcy and family breakdown. Yet again, it is important to remember that the Courts have the right to decide otherwise should the Courts feel that the Trust was created simply for the purpose of avoiding an equitable distribution of assets at any time.

a) Bankruptcy

Assets held in a family trust are held separately from any beneficiary, so they are generally protected from creditors. This can provide asset protection for clients who run their own business, have personal risk exposure through their employment or have given personal guarantees for loans.

However, where assets are transferred into the trust to defeat creditors, these assets may be available to a bankruptcy trustee. Also, despite the general protection of assets from creditors, trustees may still be liable for any actions or personal guarantees.

b) Relationship breakdowns

If a beneficiary is involved in a relationship breakdown, the trustee could exercise their discretion to direct trust distributions away from this beneficiary to reduce the property and income that would be divisible.

That said, if the trust assets are considered ‘property’ of the marriage, the assets could still be divisible in the event of a relationship breakdown. The Courts look at the substance of each case and try to identify whether the property is actually used as part of the marital asset pool, and if Courts decide so the Trust will act as a protection.4

Retirement Planning Tool

They can also be used to rebalance family wealth between spouses. For example, women often retire with less super than men if they have taken time out of the workforce to raise children. The flexibility of family trusts means they can take a greater share of trust income in retirement to make up for a smaller super balance, in a tax-effective way. 5

Under a family (or discretionary) trust structure, investment assets are held by a trustee. Trustees can pass assets or trust income at their discretion to particular beneficiaries, which could potentially include everyone in a family group.

Conclusion

As we discussed, a family trust is a great tool to have to ensure that wealth is distributed in an efficient and economic manner. However, because of the controversies surrounding some of its aspects its always better to think through all aspects and advantages in greater detail prior to launching into establishing one. In Part 2 of this Article, we will look at some practical aspects of setting up the trust and possible pitfalls one should avoid.

- Kennon v. Spry 2008 HCA 56, <http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/HCA/2008/56.html>.

- Income Tax Assessment Act 1936, <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1936240/sch2f.html>.

- Part IVA – Income Tax Assessment Act 1936, <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1936240/index.html>.

- Brooks, Alison, Protecting your (farming) property from a relationship breakdown with a Family Trust?, 27th December 2013, <http://www.mondaq.com/australia/x/283116/divorce/Protecting+your+farming+property+from+a+relationship+breakdown+with+a+Family+Trust>.

- O’Sullivan, Bernie, Family Trusts – Legal lessons to be learnt from family feuds, 7th December 2012 <http://www.familylawexpress.com.au/family-law-news/wills-probate/family-trusts/family-trusts-legal-lessons-to-be-learnt-from-family-feuds/690/> .

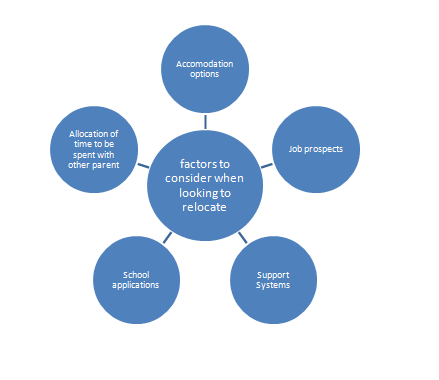

Relocation is indeed a very important aspect that tends to arise with instances of divorce.

Relocation is indeed a very important aspect that tends to arise with instances of divorce.

A ‘DNR order’ (Do Not Resuscitate) is a medical order to withhold cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) techniques.

A ‘DNR order’ (Do Not Resuscitate) is a medical order to withhold cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) techniques. Common law and legislation in some states allow for an individual to make an advance health directive, which effectively informs the patient’s health team regarding the care the patient would like in the future should the patient become unable to make medical decisions. It can cover the withholding of CPR.

Common law and legislation in some states allow for an individual to make an advance health directive, which effectively informs the patient’s health team regarding the care the patient would like in the future should the patient become unable to make medical decisions. It can cover the withholding of CPR. A child contact centre is a place co-parents can bring their children for change-overs or visitation.

A child contact centre is a place co-parents can bring their children for change-overs or visitation. I can’t speak for the whole industry, as the industry can split along political lines when it comes to this topic. From a scientist/practitioner point of view, it is important that there be clear definitions of things, and the definition above has a problem in the part about “causing the family member to be fearful.”

I can’t speak for the whole industry, as the industry can split along political lines when it comes to this topic. From a scientist/practitioner point of view, it is important that there be clear definitions of things, and the definition above has a problem in the part about “causing the family member to be fearful.”

As a general rule, yes, the child should have relationships and spend time with both parents, irrespective of age.

As a general rule, yes, the child should have relationships and spend time with both parents, irrespective of age.