Cases involving child abuse are amongst the most difficult cases faced by courts dealing with Family Law matters.

Cases involving child abuse are amongst the most difficult cases faced by courts dealing with Family Law matters.

They are equally difficult – both from an emotional and evidentiary perspective for the parties involved.

The nature of child abuse in a family context – the fact that the perpetrator is often a family member, the child is young and hence more impressionable, less aware and less accurate in their recollection of events, and the lack of corroborating evidence due to the secrecy of the abusive act – makes such cases difficult to prove. 1 , 2

However, it is is irrefutable that abuse – either past abuse or future risk of abuse, carries severe consequences for a child.

For this very reason, it is imperative that the law develops an approach to cater to the evidentiary difficulties involved in child abuse cases to ensure that children are free from abuse or risk of abuse.

Abuse is not confined to physical or sexual abuse alone. It encompasses psychological abuse and serious neglect. This is made clear in section 4(1) of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) that provides a definition of abuse in relation to a child.

The Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) also makes clear that in family law proceedings involving children, the paramount consideration is the best interests of the child.3 Under s60CG(1)(b) of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth), the court must, consistent with the child’s best interest, ensure that any order ‘does not expose a person to an unacceptable risk of family violence.’ This approach reflects that taken by the High Court of Australia in one of the more influential cases dealing with family law matters, M v M. 4

A. The ‘Unacceptable Risk’ Test In M v M

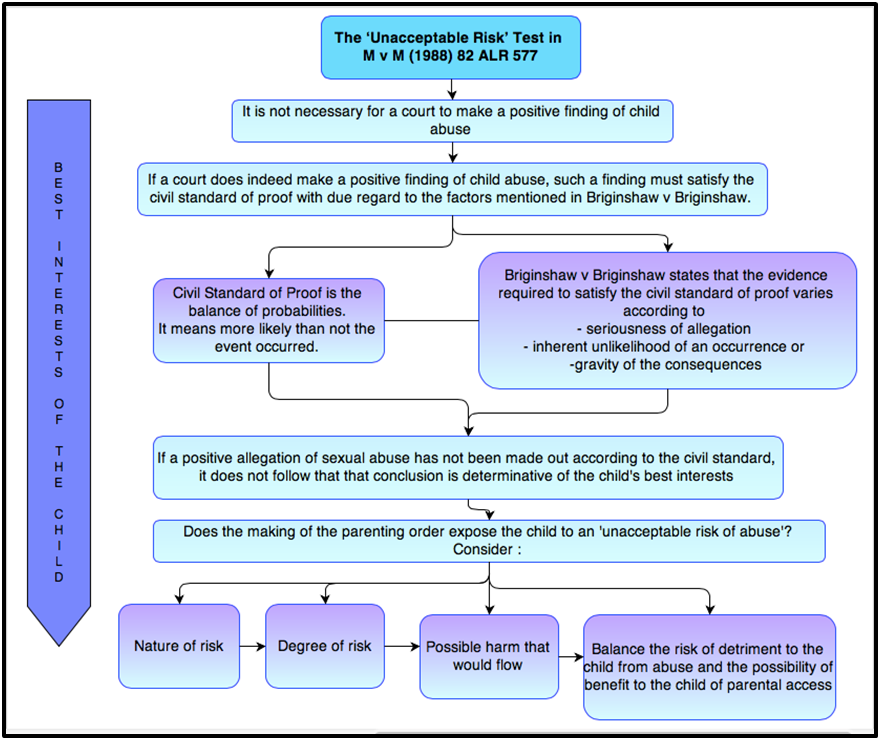

The High Court in M v M concluded that the test to be applied in making parenting orders is that ‘a court would not grant custody (now commonly termed residence or ‘lives with’) or access (now commonly termed contact) to a parent if that custody or access will expose the child to an unacceptable risk of sexual abuse.’ 5 The judgment helpfully provides the process in which this is to be determined.

Firstly, it is not necessary for a court to make a positive finding of child abuse. 6

In fact, the High Court cautioned against courts doing so. The High Court rightfully emphasised that a family law matter involving children is to be conducted as a proceeding that is directed at the risk to the child, as opposed to a criminal trial of the alleged abuser.

This is because the Family Court is not under the same duty to resolve an allegation of child abuse as a court exercising criminal jurisdiction in a trial. 7

The paramount consideration is always the best interests of the child. 8

Secondly, as a corollary to the first point, if the court does indeed make a positive finding of child abuse, such a finding must satisfy the civil standard of proof (ie balance of probabilities), with due regard to the factors mentioned in Briginshaw v Briginshaw. 9 and 10

This standard is lower than the criminal standard of proof, which is beyond reasonable doubt. Balance of probabilities requires that it is more probable than not that the alleged event occurred.

Briginshaw v Briginshaw is authority for the fact that the civil standard of proof (balance of probabilities) is not a fixed standard. The standard of proof has to cater to the seriousness of an allegation made, inherent unlikelihood of an occurrence of a given description, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding.

Depending on the nature of the allegation, the strength of the evidence required to meet the civil standard of proof may vary. The more serious the offence and gravity of the consequences, the more likely it is that the civil standard of proof cannot be satisfied by mere circumstantial or uncorroborated evidence.

Thirdly, if a positive allegation of sexual abuse has not been made out according to the civil standard, it does not follow that that conclusion is determinative of the child’s best interests 11

The fundamental issue remains the protection of the child from ‘unacceptable risk’ of abuse. ‘Risk’ of abuse essentially requires a court to assess possible future risk of abuse – hence it does not require a definitive finding that past abuse has in fact occurred.

From the evidence available, a court is required to assess the magnitude, nature and the degree of risk of abuse and the harm that may result if the abuse does occur 12.

The court then has to determine if the risk of abuse is ‘unacceptable’ such that it would justify denying access or custody to a parent. The test of unacceptable risk attempts to achieve a balance between the risk of detriment to the child from abuse and the possibility of benefit to the child of parental access. 13. However, the best interests of the child remain paramount.

B. Advantages Of The ‘Unacceptable Risk of Child Abuse’ Test

The advantage of the test of ‘unacceptable risk’ is that it caters to the nature and degree of the risk – hence it can adapt to the circumstances of a particular case and the type of evidence available.

Should the test employ terms such as ‘substantial’, ‘serious’ or ‘real’risk, these words seem to suggest a more fixed threshold. 14

The test further concentrates on the welfare of the child, consistent with the requirements of the Family Law Act rather than determining whether the alleged abuser is in fact guilty of past abuse. 15.

C. Disadvantages Of The ‘Unacceptable Risk of Child Abuse’ Test

The main criticism directed at the test is that as it allows a court to consider unproven allegations of past abuse which in turn affect the assessment of future risk of abuse. This process is at odds with the traditional premise of legal reasoning.

This type of legal reasoning ultimately provides a platform for false allegations of child abuse to be used to legally justify the removal of contact rights or parental responsibilities from one of the parents, usually the father.

Many family law court litigants fear that unproven, unlikely and possibly irrational child abuse allegations can be used to justify cessation of contact with the victim parent’s children, not because of the veracity of the allegations, but because of their magnitude.

As retiring Family Court Judge, Justice David Collier recently lamented in a news article:

“Once an allegation has been made it is impossible to ignore. The court must deem whether there is an ”unacceptable risk” of abuse occurring in the father’s care.”

“Sometimes the allegations are obviously fabricated, other times they are probably true.”

”It’s that grey area in the middle that you lose sleep over at night, and you do lose sleep,” 16.

Legal decisions ought to be made on the basis of proven facts as opposed to a ‘crystal ball’ exercise based on mere on suspicion and unproven facts. 17 and 18

Furthermore, the test also offers little certainty in outcome. This is because it effectively requires an assessment of future risks and balancing of the risk of detriment to the child from abuse and the possibility of benefit to the child of parental access.

Hence, it has to be accepted that the adjudication of these cases can produce different outcomes depending on how the evidence is evaluated and the interplay of subjective considerations. 19

Conclusion

Despite criticisms of the ‘unacceptable risk’ test, the judgment of the High Court in M v M is binding upon all lower courts in Australia. 20

The test certainly does cater to the requirement of section 60CA Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) that a child best interest is to remain the paramount consideration.

What is required is further development on the principles emerging from the test in a way consistent with the judgment of the High Court and the best interest of the child. This would offer further guidance to lower courts and parties involved in understanding and applying the test.

Related Family Law Judgments

- Watson & Burton [2015] FamCA 549 - Family Court of Australia - Tree J - 16/07/201... - July 16, 2015

- Huffman & Gorman [2015] FamCA 317 - Family Court of Australia - Hannam J - 29/04/... - April 29, 2015

- Helbig & Rowe [2015] FamCA 146 - Family Court of Australia - Rees J - 09/03/2015... - March 9, 2015

- Thornton & Thornton [2015] FamCA 92 - Family Court of Australia - Murphy J - 23/0... - February 23, 2015

- Ridgely & Stiller [2014] FCCA 2668 - Family Court of Australia - Judge Bender - 1... - November 19, 2014

- Mitchell & Mitchell [2014] FCCA 2526 - Family Court of Australia - Judge Harman -... - November 14, 2014

- Wylie & Wylie [2013] FamCA 426 - Family Court of Australia - Tree J - 07/06/2013... - June 7, 2013

- Carpenter & Carpenter (No. 2) [2012] FamCA 1005 - Family Court of Australia - 29/... - November 29, 2012

- Wang & Dennison [2009] FamCA 206 - Family Court of Australia - Bennett J - 20/03/... - March 20, 2009

- Stephen Page, The Family Court And Child Abuse.

- Matthew Myers, Towards a safer and more consistent approach to allegations of child sexual abuse in Family Law Proceedings – Expert Panels and Guidelines.

- s60CAFamily Law Act 1975 (Cth)

- M v M (1988) 82 ALR 577.

- M v M(1988) 82 ALR 577, 583.

- M v M (1988) 82 ALR 577.

- M v M (1988) 82 ALR 577.

- s60CA Family Law Act 1975 (Cth).

- Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 362.

- M v M (1988) 82 ALR 577.

- M v M (1988) 82 ALR 577, 588.

- M v M (1988) 82 ALR 577, 588.

- M v M (1988) 82 ALR 577, 583.

- John Fogarty, ‘Unacceptable risk — A return to basics’ (2006) 20(3) Australian Journal of Family Law 249.

- Patrick Parkinson, ‘Family Law and Parent – Child Contact : assessing the risk of sexual abuse,’ Paper presented at the Third National Family Court Conference, Melbourne 21 October 1998.

- False abuse claims are the new court weapon, retiring judge says.</a>

- Patrick Parkinson, ‘Family Law and Parent – Child Contact : assessing the risk of sexual abuse’ – Paper presented at the Third National Family Court Conference, Melbourne 21 October 1998.

- John Fogarty, ‘Unacceptable risk — A return to basics’ (2006) 20(3) Australian Journal of Family Law 249.

- John Fogarty, ‘Unacceptable risk — A return to basics’ (2006) 20(3) Australian Journal of Family Law 249.

- John Fogarty, ‘Unacceptable risk — A return to basics’ (2006) 20(3) Australian Journal of Family Law 249.

Manisharaj Kaur Pannu

Latest posts by Manisharaj Kaur Pannu (see all)

- Unacceptable Risk: Standard of Proof in Determining Child Abuse in Family Law - October 6, 2014

- Do Not Resuscitate: Who Decides? - August 19, 2014

- Overnight Care for Under 2 Year Olds: Unravelling the Controversy - July 1, 2014