Although the effects of alcohol consumption in smaller quantities during pregnancy remain scientifically dubious, a local authority in England recently requested damages compensation on behalf of severely disabled seven-year-old girl.

Although the effects of alcohol consumption in smaller quantities during pregnancy remain scientifically dubious, a local authority in England recently requested damages compensation on behalf of severely disabled seven-year-old girl.

The local authority applied to the government’s criminal compensation authority arguing that the mother’s heavy alcohol consumption during pregnancy resulted in her daughter being born with severe damage and deficiencies.

Though there was no hint of charges being brought against the girl’s mother, the local authority argued that the mother’s consumption of up to half a bottle of vodka and eight cans of strong lager a day during pregnancy was “reckless”, especially after she had discussed her drinking with medical professionals.

Even though she was warned of the risks, she continued drinking heavily.

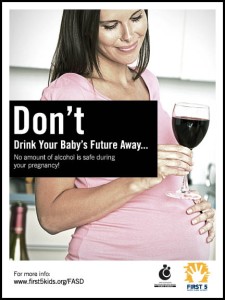

The girl exhibits a severe form of foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). FASD is an umbrella diagnosis that encompasses a range of disorders such as reduced intellectual ability, organ problems, restricted growth, mental health and behavioural problems, and birth defects.

Additionally, all children with FASD have abnormalities of brain structure and/or function.

The Court of Appeal eventually ruled against the claim, stating, “We have held that a mother who is pregnant and who drinks to excess… is not guilty of a criminal offence under our law if her child is subsequently born damaged as a result.”

For the claim to be successful, the Court would have had to rule that the mother was guilty of behaviour that constituted a crime.

For this case, that crime was the alleged reckless administration of a noxious substance to the foetus.

Though the matter seems to be settled on a legal level, there exists a lingering feeling of moral discomfort.

It is undisputed that alcohol increases the risk of harm to an unborn baby, and this risk is greatest when, as in this case, the mother frequently drinks large amounts.

But can heavy drinking during pregnancy be considered criminal?

Ann Furedi, who heads the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS), and Rebecca Schiller, co-chair of Birthrights (a human rights in childbirth charity), praised the Court’s ruling in this case.

“The UK’s highest courts have recognised that women must be able to make their own decisions about their pregnancies,” they said in a joint statement.

In Australia, advice given to expectant mothers changed in 2009. Drinking guidelines now strongly advise abstinence from alcohol during pregnancy.

However, there is confusion, as the guidelines previously advised that no more than two standard drinks a day and less than seven days a week would be safe for the unborn baby.

This confusion, in addition to anecdotal evidence ofobstetricians still telling their patients that the occasional drink is fine – in defiance of what the guidelines advise – may be contributing to a recent study that found that almost eight out of ten pregnant women admitted to consuming alcohol.

Many studies regarding the effects of low-level drinking (defined as one to two standard drinks per occasion but less than seven standard drinks a week) have proved either inconclusive, or unreliable due to weaknesses in the studies.

However, Dr. Colleen O’Leary, one of Australia’s leading alcohol and pregnancy researchers, stressed that despite the lack of clear evidence of harm from low-level drinking, current guidelines are right in recommending pregnant women stay away from drinking completely.

Because there is “such a small margin” before risk to the foetus is definitely increased, and it is very easy to drink more than one realises, she stated that, “it would be morally and ethically unacceptable” for guidelines to condone any drinking during pregnancy.

Much research still hints at even low-level drinking during pregnancy causing defects in children, such as poorer performances in school tests by age 11, or loss of up to four IQ points in the child.

Stay Informed. It’s simple, free & convenient!